In Switzerland, there are not enough general practitioners available to meet the needs of the population.

Have you ever tried calling a GP, only to hear the voicemail keep telling you, even after a dozen times, that no appointments are available unless you’re already a registered patient. Maybe you’ve done what some others have done and actually scanned the obituaries, where the GP is often thanked. You can then object, saying, “I know you have a spot, because one of your patients has died.” In 2021, a survey by the French-speaking Swiss Consumer Federation showed that, depending on the region, it can take up to 30 tries to get an appointment. This situation is likely to get worse over the next few years as the population ages and the shortage of new doctors grows. The Swiss Society of General Internal Medicine estimates that the number of general practitioners in practice in Switzerland will decrease by about 2,300 between now and 2033. “We need general practitioners,” says Stéfanie Monod, Vice-Director of the École de formation postgraduée médicale at Lausanne University Hospital, “and these family doctors who are close to people are an essential link in the chain.” Universities are devoting more time to primary care medicine, and work is being done to create a more positive working environment for general practitioners. Cooperation is also being improved between professions. But we need to move fast, because medical studies take a long time.

1. Real-life consequences of the GP shortage

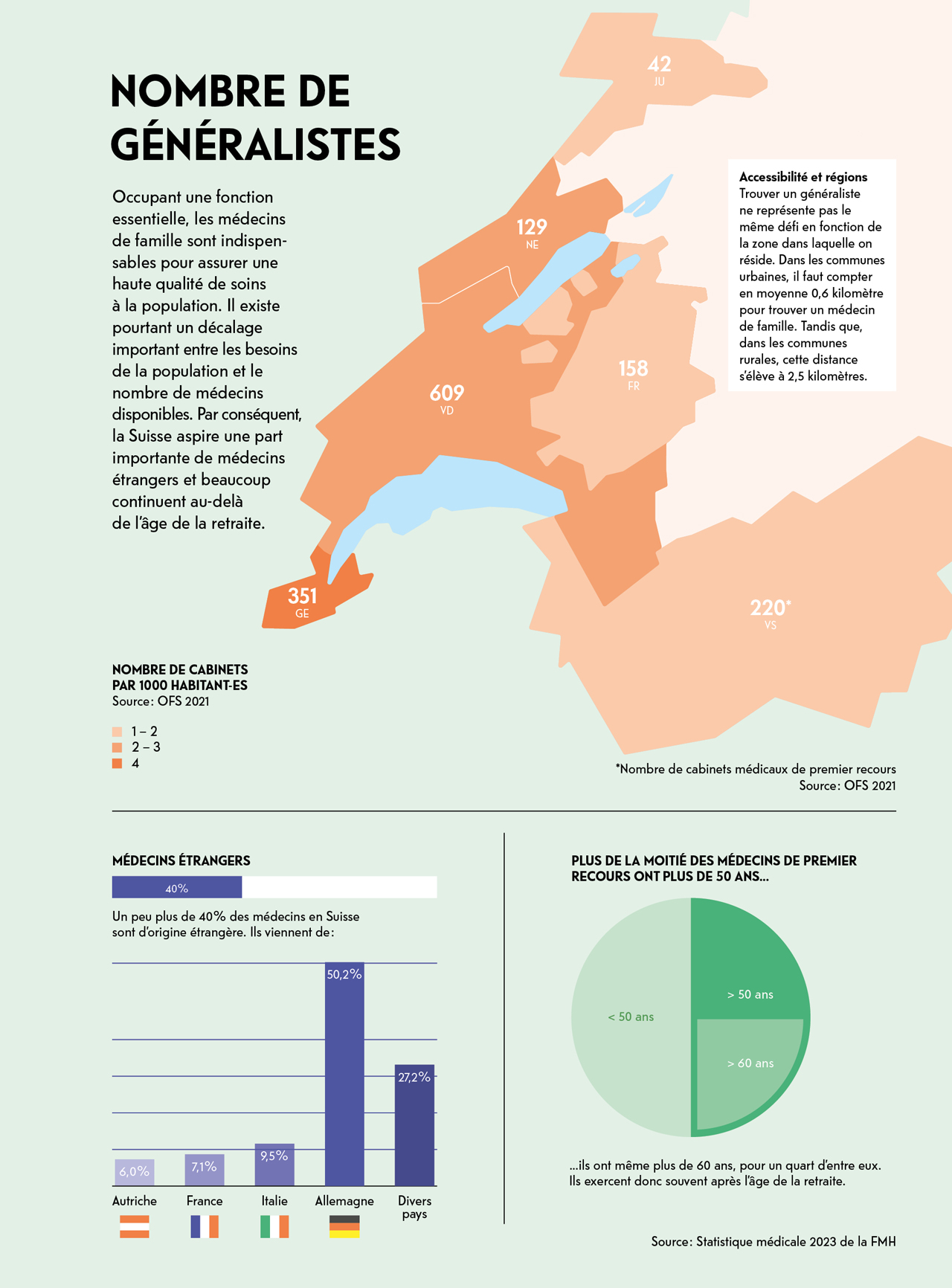

In Switzerland, the gap is growing between supply and demand for trained doctors. And even though the 2023 medical statistics from the Federation of Swiss Physicians (FMH) show a slight increase (800 full-time equivalents more than the previous year), the organisation points out that this increase will not be enough to make up for the shortage of qualified staff. In addition to the overall shortage of doctors, there is a shortage of specialists in primary care medicine, which includes paediatricians, gynaecologists, psychiatrists and family doctors.

OVERCROWDED EMERGENCY ROOMS

This shortage is a direct threat to the vitality of the healthcare system. If no general practitioners are available, people with health problems go to the emergency room. This choice is particularly problematic, because it overburdens emergency services and contributes to inflating healthcare costs. What’s more, the system is not designed to provide the best response to most of the problems for which people come for medical care. “People often believe that easy access to emergency services is the right thing to do,” says Sébastien Jotterand, a GP in Aubonne and co-president of the organisation Médecins de famille Suisse. But it’s not. The role of the emergency room is primarily to address life-threatening conditions, but not necessarily to figure out the exact cause.” Furthermore, going to the emergency room means continuously starting all over again, as you have to explain your health history to the doctor you are seeing for the first time. Sébastien Jotterand also highlights how much information about the person’s state of health and any treatments administered can get lost in the process if the patient has no GP.

Choosing not to seek medical care

When emergency services substitute a GP, access to care gets complicated. Emergency rooms are organised first and foremost to handle acute health problems. Consultations for symptoms that cause discomfort but are not life-threatening mean that patients can expect long waits. “Not only does this overcrowd hospitals, which are already under strain, but it leaves no space for prevention, which is vital for a healthy population,” Stéfanie Monod says. “In addition, limited access to primary care can deter people from seeking care at all.” Obviously, no one would be admitted to the emergency room to have a check-up or get health advice. Therefore, patients without a GP simply do not receive preventive care.

Well, this procrastination has serious consequences for the healthcare system. The longer people wait, the more complex and expensive medical procedures and interventions become. What results is a downward spiral in which the GP shortage leads to a huge lack of preventive care, and potentially to more sick people requiring even more doctors for treatment. However, it has been proven that primary care medicine can not only play an essential role in prevention, but also solve 94.3% of health issues while accounting for only 7.9% of healthcare costs, as highlighted by the 2020 Primary Care Physician Workforce study from the Basel University Centre for Primary Care Medicine.

FIGURE

Number of people in Switzerland who feel there is a shortage of doctors at the regional level, according to a 2022 survey conducted by the magazine DOC, published by the Société vaudoise de médecine.

Attracting doctors from abroad

To try and balance things out, Switzerland hires a huge number of foreign-trained physicians. The Federation of Swiss Doctors reports that 40% of practitioners come from other countries. This practice raises ethical questions, because by hiring doctors from abroad, Switzerland benefits from other countries’ investment in training. These countries cannot reap the benefits, since their young doctors leave once they become professional.

However, even in training, spots are limited. To start studying medicine at university, you not only have to pass your exams but also rank among the top students. This is known as the numerus clausus, which limits the number of people who can study medicine each year. It means that students can pass the exam without being guaranteed a spot.

Some Swiss students study abroad, especially in Romania. In 2004-2005, only 13 students were interested in this alternative, compared with 111 in 2023. Once they complete their studies, young doctors systematically return to Switzerland to practice.

Postponing retirement

The challenge of finding a family doctor is a reality faced by the general public. But it also affects general practitioners, who cannot retire because no one can replace them. Last January, the television programme Mise au point went to Hauterive in the canton of Fribourg to meet general practitioner André Schaub. He hopes the handover of his practice to another GP will go smoothly. Providing an office and an interest-free loan of 300,000 Swiss francs was not enough to attract a new doctor.

André Schaub is not the only one experiencing difficulty. Ageing GPs, and therefore their retirement within the next few years, are cause for concern. Based on the register of medical professions, RTS reports that more than one in three general practitioners is over 60.

So how can we explain why this speciality, which combines advanced scientific knowledge and strong people skills, and which plays such a vital role in ensuring that the healthcare system works properly, interests so few people to the point of causing a shortage?

2. A closer look at the lack of interest in medicine

General internal medicine has a bad reputation. It is often contrasted with specialised medicine but should not be. In people’s minds, general practitioners are believed to be unspecialised, i.e., they stopped their medical training earlier than the rest, giving up the opportunity to specialise in surgery, urology or oncology. But that is not true. It takes the same number of years to qualify as a family doctor with a practice as it does to operate on a heart. “We too often forget that GPs are specialists in general internal medicine,” Stéfanie Monod says. “This field is often unjustly believed to be easier, but it is just as complex, if not more so, than any other speciality.”

Hospital-based training

In terms of training, primary care medicine is struggling to find its place. Most of the training focuses around the hospital, where future doctors do most of their internships. Then, during postgraduate training (i.e. after university), their first years in the profession are also spent in hospital.

This hands-on experience can be extremely intense. For example, young doctors work long hours and are potentially subject to considerable stress and an administrative work overload. They can become disillusioned with family medicine in a practice, for which they not only have their duties as a doctor, but must also invest in an office for consultations and in staff.

“A hierarchy has been established in which the profession of general practitioner is not held in the highest regard”

Simon Golay, 23, is a third-year medical student and President of the Lausanne Medical Students’ Association. He discusses how he feels about his training and what he sees in the training around the profession of GP.

![[Translate to Anglais:] Photo: Heïdi Diaz](https://www.invivomagazine.ch/fileadmin/documents/images/_Dossiers/Le_systeme_de_sante_en_danger/54217_24_DDIR_COM_IN_VIVO_GOLAY_Simon_049.jpg)

“As a student, it’s particularly difficult to understand why training is so demanding, while, at the same time, so few people can access it when we have a shortage of doctors. And yet the studies are still attractive. I get the feeling that social value is still attached to the profession. The image of the white coat, forged mainly by TV series and social media, retains its appeal. Many people go into this profession inspired by their parents, who are doctors. For my part, it was the Swiss surgeon and researcher Jocelyne Bloch who inspired me to take up this profession.

However, it’s true that general internal medicine with the aim of becoming a general practitioner is not the most sought-after specialisation. These days, a sort of hierarchy (which has no basis) has been established, in which the profession of general practitioner is not held in the highest regard and therefore is not the most popular, unlike other specialities such as cardiology. In France, this relationship is made worse by the fact that the students with the lowest marks have to settle for specialities that were not chosen by the top students – often general medicine – while the other specialities are reserved for the brightest.

At university, most courses are taught by leading experts, specialists who are often passionate about their field. Their devotion inspires us and invites us to choose their speciality, which gives us a very early idea of what we might want to do in our career. This contrasts sharply with the final exam, which is a general medicine exam.

It is also interesting to note that students from the University of Fribourg always get the best scores on the federal exam, although most of their courses are not taught by specialists. If more courses were taught by GPs in the first years of medical school, we might be encouraged to consider this speciality earlier in our career. I think that we would attribute greater value to general medicine if we had more opportunities to work in a primary care doctor’s office earlier in our training.

Then there is the psychological aspect. The inherent demands of medical school require us to put part of our lives on hold while in training. We are forced to contend with some daunting considerations, such as how we feel about death, which we are confronted with regularly. I think that the pressure of training and the heavy workload encourage some people to choose a speciality that promises a more comfortable lifestyle, financially speaking. Meanwhile, others prefer an academic career with plenty of potential for advancement in a given specialisation. This is less of an option when you go into general medicine.”

Heavy administrative burden

“In recent years, the administrative burden on GPs has become heavier,” says Vanessa Kraege, Vice-Director and Head of Operations at the École de formation postgraduée médicale. “For example, more and more companies ask their staff for a medical certificate after just one day of absence, whereas patients will spontaneously feel better within a few hours. Care administered by GPs also has to be documented in a much more bureaucratic way than in the past, with insurance companies often requiring justification. This increase in administrative tasks is not only a waste of time, but also takes away meaning.” The heavier administrative burden is not just affecting GPs, but the whole profession. It is pushing doctors to quit the profession, especially younger ones. Of the 30% of doctors who are leaving the profession, 35% are under 35 and some have not even completed their postgraduate training.

In successful television series, such as “Grey’s Anatomy”, characters rarely have to deal with the heavy administrative burden, for example.

However, the predominant role of the hospital in these fictional dramas reflects the reality of doctors’ training, which focuses on the hospital setting rather than experience in a primary care practice.

Differences in income

The shortage also contributes to creating tougher working conditions. In the case of general practitioners, with fewer of them in practice, the number of patients they care for increases. This in turn creates a heavier workload, which makes the profession less attractive. Considering these challenges, the pay gap between GPs and other specialists plays a major role. “We urgently need to find more ways of paying for certain activities,” says Philippe Schaller, co-founder of the Groupe Médical d’Onex in Geneva. Under the current fee-for-service system, coordination, prevention and therapeutic education are not covered. Yet they are an essential part of what GPs do.”

As a result, under the current pricing scales, a procedure performed by a GP, for example, is worth less than one performed by a dermatologist. As a result, internal medicine is highly undervalued financially compared with other specialties and is becoming even less attractive to young doctors in training.

3. How to strengthen primary care medicine

“Society needs to figure out what kind of medicine it wants,” Vanessa Kraege says. “Self-service medicine, available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, where you can get whatever you want, or quality medicine based on common sense that retains some degree of humanity?” If the profession of general practitioner is to regain its appeal, action should be taken on training. For example, by offering more internships in practices, to provide a more accurate view of this area of medicine. Course content should also be adapted. “There are too many highly specialised lecturers in the university curriculum,” Stéfanie Monod says. “Today, training is still too focused on diseases that future doctors will see very little of during their career.” Rethinking training is therefore essential. Vanessa Kraege agrees. “We need to find ways of training doctors non-stop to keep up with the constant advances in science, at a time when science is becoming increasingly complex and doctors have less and less time. Doctors need to acquire new tools, such as cybersecurity knowledge to protect their patients’ records or the proper use of artificial intelligence. They also need to know how to use all the functions of a new software package or stay informed about ethics and sustainability issues.”

FIGURE

Percentage of health problems that GPs can solve. And they can do that while accounting for just 7.9% of healthcare costs, according to the Workforce 2020 study on primary care.

Working together, creating new structures

After training, we also need to rethink the way we work together. “Primary care doctors work alone less and less,” Philippe Schaller says. “They are looking to join forces and are therefore opting for interprofessional organisations. This also allows them to work part-time and avoid excessive financial expenses.” This is what places like the Cité Générations medical centre in Geneva are aiming for. The facility opened in 2012, under the impetus of Philippe Schaller. This hybrid medical centre is somewhere between a doctor's office and a hospital, helping to take some of the burden off outpatient emergency services. It also has 10 inpatient beds, a first in Switzerland. “For the general public, these health centres offer a number of advantages: extended hours for medical appointments every day, shared medical records between the different disciplines, and specialist consultations if necessary. The follow-up of patients with chronic illnesses is coordinated better.” This model also reduces the administrative burden on doctors’ schedules. Above all, it facilitates interprofessional collaboration, a key factor in combating the shortage of qualified care staff, by bringing together a team of nurses and pharmacists who can carry out certain medical procedures. “Healthcare centres offer a valid solution to the growing number of people suffering from increasingly complex chronic illnesses. Family doctors who want to retire can comfortably and easily transfer their patients, who already know how these centres handle their care.”

Finally, these days, when people are subject to extreme anxiety, where wars are compounded with a worsening economy and environment, a functioning healthcare system is vital. Recently, a research team from the University of Copenhagen estimated that 82.6% of women and 76.7% of men will be affected by mental health problems in the coming years. As GPs are often the first point of contact for people with mental health issues, their role in providing early support for this subgroup is essential.

Steering future doctors towards the specialists that people need most

Reorganising training can help combat the shortage of general practitioners in Switzerland. A closer look.

Switzerland’s Réformer project tackles the gap between supply and demand for trained doctors. The aim, for example, is to limit the disparity between the number of family doctors and those in other specialities. “The tool we are developing does not affect the content of training courses, but rather the way in which future doctors are guided and supported when they choose their postgraduate training, i.e. once they have completed the university training specific to their speciality,” says Nicolas Pétremand, Director of Réformer.

To propose effective responses at the level of medical resources and the French-speaking cantons, the first thing to do is to clarify needs. “Our first priority is to obtain a better picture of current medical demographics and postgraduate training pathways. We also lack coherent, documented figures on the distribution of different specialities according to needs. They need to be estimated based on the current situation, demographics and medical trends.”

In practical terms, Réformer wants to introduce a better system of support for postgraduate training. “Like coaching, senior doctors who are clear about current public health issues would help future doctors to develop a career plan that corresponds to their desires and steers them towards the specialities that the population needs most.” This is because, at present, chiefs of hospital specialties come looking for students or residents for their services. This pattern can lead to a form of wandering that prevents the specialties that need strength from being filled, and excessively prolongs the training period. “Doctors in postgraduate training thus find themselves in a loop, applying for one post after another. The system benefits from this by paying these profiles poorly, because they have not yet completed their specialist qualifications.”

As well as strengthening the healthcare system by aligning specialisations with the real needs of the population, this system also helps to combat discouragement among young doctors, by giving family medicine and general internal medicine a better image. “By providing a resource person (coach, career mentor, pathway coordinator), it’s easier for future specialists to think of new solutions if the direction they initially wanted to take doesn’t turn out to be the right one for them, or if they feel they’re having difficulty coping with the pressure of committing to a service. It also enables them to get neutral support from a peer who is not the one validating the acquisition of skills.” Priority is being given to the quality of support for doctors in postgraduate training who are hesitating or changing direction, and to the information they need to make an informed decision. This tool will make it possible to produce data and indicators that are currently lacking for steering the system, ideally at national level. “This information will be useful for doctors in training, the establishments and institutions responsible for training doctors, and the cantons, which must ensure that the needs of their populations are met.”

General practitioners

![[Translate to Anglais:] Photo: Heïdi Diaz](https://www.invivomagazine.ch/fileadmin/documents/images/_Dossiers/Le_systeme_de_sante_en_danger/54217_24_DDIR_COM_IN_VIVO_GOLAY_Simon_049.jpg)

![[Translate to Anglais:] Photo : Gilles Weber](https://www.invivomagazine.ch/fileadmin/_processed_/e/e/csm_54217_24_DDIR_COM_IN_VIVO_JOTTERAND_Sebastien_7487_f09905558e.jpg)