No social class or background is spared. Sexual violence against minors is omnipresent.

Cousin, granddaughter, best friend, neighbour, colleague... We may not realise it, but most of us know someone who was sexually abused as a child. We have also heard stories of a father, who too often sneaks into his daughter’s bedroom while the rest of the family is asleep, or of a teenager, who harasses his cousin and insists on calling it “kids’ games”. We know these people yet sometimes have no idea what they have gone through or choose to ignore it. It is easier to look away than to face the reality of these assaults. Although people have begun to speak more freely about sexual assault since the #MeToo movement, taboos surrounding sexual abuse of children – especially incest – are powerful and paralysing.

Nearly one child in five is a victim of sexual assault, estimates the Council of Europe, the leading human rights organisation in Europe. Touching. Exhibitionism. Harassment. Assault. Rape. Even exploitation in the form prostitution. The spectrum of sexual violence is wide and permeates every level of society. In Europe and North America, one in ten children is a victim of incest, i.e. sexual relations with a blood relative. In Switzerland, a 2019 study by Radio Télévision Suisse reported that about 350 children are victims of incest every year. The trend is stable, but the article says that “the figures only show the tip of the iceberg”. In fact, there is currently no institutional survey of incest in Switzerland. The percentage of abusive mothers is also underestimated. However, as with other types of sexual violence, 94% of aggressors are men, and around one-quarter of them were minors at the time the incident took place.

“Sexual abuse of minors is a common problem and is most likely underestimated,” says Francesca Hoegger, paediatrician and clinic head with the CAN Team, a unit at Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV) that supports healthcare professionals in identifying and assessing situations of maltreatment involving minors. As they are vulnerable and easily influenced, children are easy targets. “The notion of sexuality for very young people doesn’t have the same meaning as for an adult. And sexual abuse does not necessarily involve violence.

Many people either don’t remember what happened to them or realize much later that it was sexual abuse,” Francesca Hoegger says. This is even more poignant when children with disabilities are involved. They run a high risk of abuse and may have difficulty expressing themselves or understanding a particular gesture, for example, by someone responsible for their care. The CHUV paediatrician stresses the importance of being able to talk about it when a clinical examination of the genital area does not always render evidence. “We only find lesions in 30% of cases of abuse involving physical contact. That is why a child’s spontaneous comments are often the most telling.”

One in five children are victims of sexual abuse

This estimate by the Council of Europe is the result of a combination of several studies and statistics published by Unicef, the International Labour Organization and the World Health Organization. This figure takes into account the fact that cases of sexual abuse are often under-reported.

Source: Libération, “D’où vient l’estimation selon laquelle un enfant sur cinq a été victime de violences sexuelles?” (Where does the estimate come from saying that one out of five children has been a victim of sexual violence?), 9 November

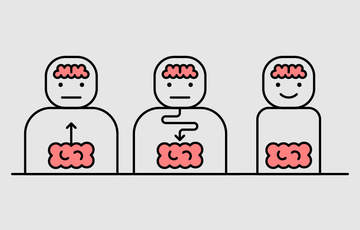

The phenomenon of “dissociation”, which can also occur with other types of trauma, is one of the keys to understanding the “traumatic amnesia” experienced by many victims of sexual abuse who are unable to speak. This reaction of physiological survival occurs when the violence is overwhelming (and can even cause a “stress-induced death”), paralysing higher mental functions and completely cutting off the emotional response. The person feels as if they are “beside” or “above” their body. Its counterpart, known as traumatic memory, can bring past events buried in the subconscious to the surface at any time. Assaults frequently return in the form of flashbacks, in adulthood, and can be triggered by an odour, a place or a colour that reawakens old traumas. On top of these physiological reactions is the hierarchical and relational context surrounding these cases of abuse. As between 70% and 85% of children know their abuser, victims can find it even harder to speak out.

INCEST: SILENCE AND DENIAL

“The family is the main sphere in which sexual abuse and violence takes place. Incest often occurs within a special relationship between an abusive adult and a child,” says Alessandra Duc Marwood, psychiatrist and senior physician at Les Boréales, a counselling centre created in 2010 to address issues of domestic violence. “Children are victims of violence at the hand of figures who represent protection and security. This causes confusion about the individual who is supposed to protect and provide love but in fact does them harm. We learn the rules about how relationships work within our family. How can they know what’s normal and what’s not?” the psychiatrist says. This point is also highlighted by French journalist Charlotte Pudlowski in her painstaking investigation based on a real-life family experience, Ou peut-être une nuit – Inceste : la guerre du silence (Or maybe one night – Incest: the war of silence)1. “We don’t rebel against people we love. That’s what makes incest such a powerful weapon of domination.”

Racked with shame and guilt, young victims remain agonisingly silent when they know that opening up about a situation of abuse committed by someone close to them means jeopardising the “tight-knit” family unit. “In families where incestuous acts exist, words are more punishable than actions,” Alessandra Duc Marwood says. In her essay, Charlotte Pudlowski also writes, “The more the person feels love and respect, with a sense of indebtedness and dependency, the greater the risk of obliterating their foundation, loved ones and family, and the more impossible it becomes to rebel. Accusation seems unmanageable, or cannot be right away, or will be too late, or come at the cost of being excluded from the home.” This wall was faced by Marjorie, 34, who was abused by her cousin from the age of 4 to 10: “He used to shut me up, telling me that it was dirty, and that if I told anyone, everyone would think I was dirty too. I once tried to tell my grandmother, but she didn’t react.” Denial from spouses and relatives is common with cases of incest. They often go so far as taking the perpetrator’s side, the psychiatrist says. Heidi experienced this disavowal from her mother, when her mother found out that her own husband had abused her daughter for years. “At first, she was sorry, but then she blamed me, accusing me of having purposely seduced my stepfather,” the 22-year-old student says. She has since cut off any ties with her mother.

1 "Éd. Grasset, 2021"

Non-contact sexual assault

• Exhibitionism

• Voyeurism

• Unsolicited exposure to pornography

• Verbal harassment

With physical contact

• Without penetration: touching, masturbation by the perpetrator on the victim or to the victim.

• With penetration: unwanted oral, vaginal or anal penetration by the perpetrator on the victim or of the victim.

Sources: LAVI CentreLAVI-Abus-sur-mineurs-pdf, memoiretraumatique.org

Aggressors are also frequently in denial, Alessandra Duc Marwood says. “Many perpetrators of violence confess to the acts but deny any responsibility. We need to remind them that a child never consents to or asks for sexual favours.” Professionals then need to work carefully with the abuser to get them to acknowledge the facts, reminding them of the law and, more importantly, helping them to realise the impact of incest.

A matter of public health

While the number of cases of sexual violence on minors remains underestimated, their repercussions on public health are quite tangible. A 2018 study in the United States2 estimated that child sexual abuse cost the country more than $9 billion in economic losses. This figure covers healthcare, child welfare services, special education, violence, crime, suicide and productivity losses of the abused. “We’re not created equally when it comes to risk or resilience. But we do know that having experienced violence or abuse has a negative impact on the future,” says Alessandra Duc Marwood. The ramifications are even worse if risk factors are compounded (social isolation, illness, poverty, etc.).

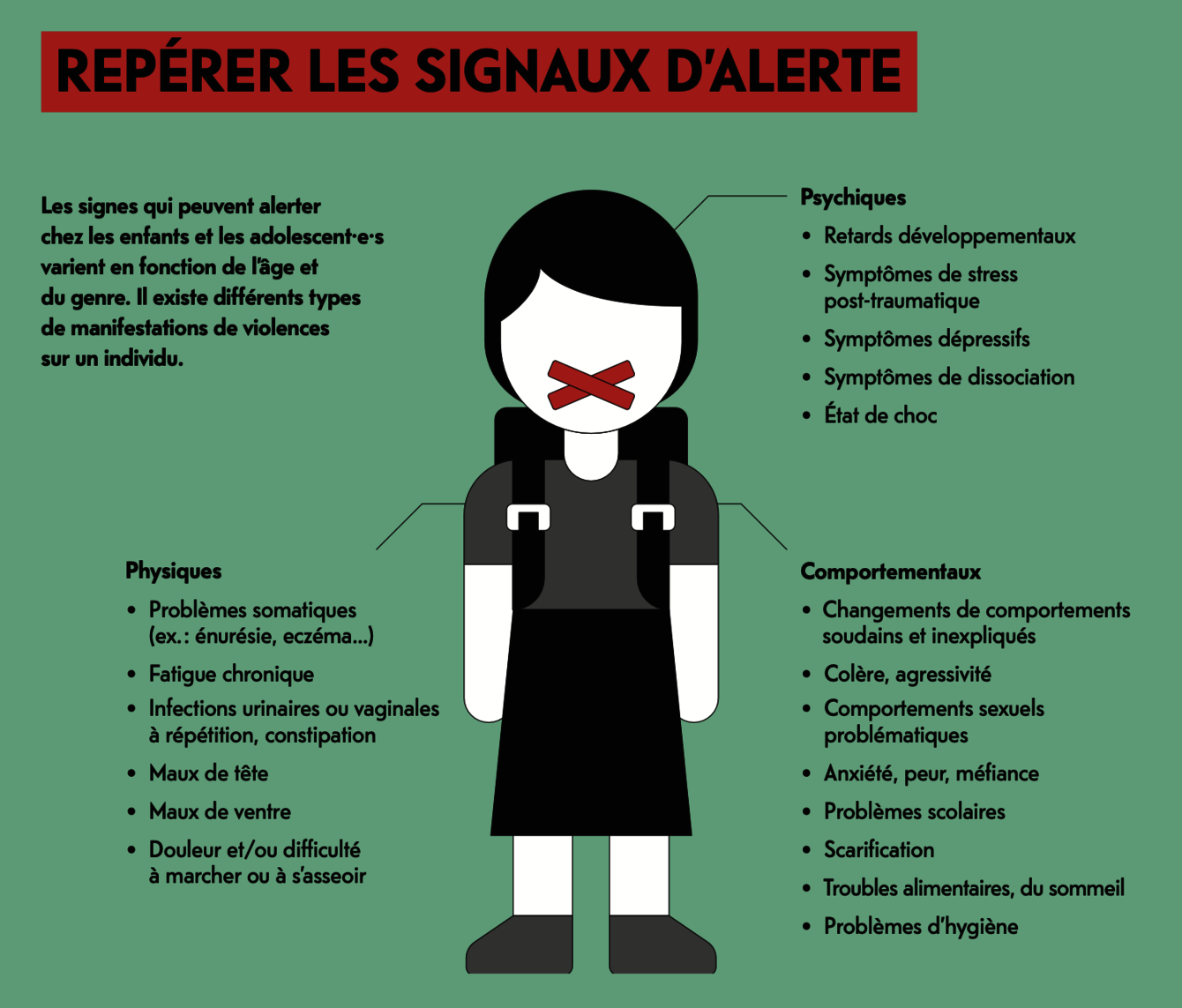

The damage that children come away with varies with individuals and their gender. It may take the form of shock, anxiety, aggression, developmental delays or neurobiological manifestations. The after-effects often last into adulthood and future generations, which is even more likely if the abuse is repeated. It can result in attachment problems, OCD, aggression, addictions, risky sexual behaviour, chronic illness, social isolation, and the list goes on. For Marjorie, the abuse perpetrated by her cousin resulted in bouts with anorexia and bulimia, problem drinking and difficulties with intimacy. “To this day, I still use pretty childish expressions to talk about sex, or I simply try to avoid talking about it. I always feel like I’m doing something wrong or dirty,” the young woman says, and her hang-ups have ruined many of her relationships. As for Heidi, she remembers having her first period very early, at the age of 9. “As a child, I was already dressing as if I was older. I would wear lipstick. My stepfather used to buy me grown-up clothes.” She, too, struggles with her sexuality and suffers from flashbacks.

Less well known consequences are cardiovascular problems in adulthood that may also stem from trauma, including sexual abuse. “Regardless of the type of mistreatment, a victim of abuse is more likely to be in a constant state of hypervigilance due to post-traumatic stress disorder and live with continuously high levels of adrenaline and cortisol,” says Marco Tuberoso, psychologist at Espas, an organisation that works with child and adult victims of sexual abuse. The essay “Ou peut-être une nuit” (Or maybe one night) tells the story of Lydia, 48, who developed a degenerative neurovegetative disease following repeated psychological trauma due to sexual abuse by her father. She is now in a wheelchair.

“Suffering sexual assault doesn’t always mean a bad prognosis for the child’s future development,” Francesca Hoegger says. “But finding the necessary support helps them to get better. The earlier the child is taken into care, the less the abuse is likely to impact their future health.” Alessandra Duc Marwood treads more lightly, acknowledging that “many former victims build a life for themselves and go on to do wonderful things. But at the cost of tremendous suffering.”

² «One Year’s Losses for Child Sexual Abuse in U.S. Top $9 Billion, New Study Suggests» | Johns Hopkins | Bloomberg School of Public Health (jhu.edu)

Lexique

Sexual abuse

Any sexual activity that is inappropriate for the child’s age, psycho-sexual development and status in society.

Sexual aggression

A sudden and brutal sexual attack on an individual causing physical and/or psychological harm.

Sexual violence

Included as a form of child abuse, sexual violence includes direct physical contact and acts, which take place through visual, verbal or psychological interaction.

Dissociation

Involuntary detachment from emotions to disconnect oneself from suffering. Impression of absence from oneself at the time of the violence.

PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological reaction brought about by an experience that threatens and/or harms a person’s physical and/or psychological integrity. May be expressed, for example, as hypervigilance or flashbacks.

Traumatic memories

Psychological consequences of traumatic stress. These flashbacks, sensory illusions, nightmares cause the individual to relive the trauma and experience the same distress and the same physiological, somatic and psychological reactions as during the event.

Resilience

The ability to live and develop in a positive and socially acceptable manner, despite stress or hardship.

Help for adults concerned about

Sometimes society is more comfortable healing wounds than preventing them. It can feel easier to take care of victims rather than asking who their aggressors are, why they act, and how such violence, decade after decade, can eat away at our societies in total impunity. That way, we avoid staring straight into the face of the people we know who have committed the unspeakable. Some organisations have boldly set out to get to the root of the problem, such as Dis No, an organisation discreetly operating out of the second floor of a residential building in the centre of Lausanne.

The mission of this organisation, the only one of its kind in French-speaking Switzerland, is to help teens and adults concerned about their sexual fantasies about children (commonly referred to as “paedophilia”) and who risk acting on these urges. The problem affects approximately 1% of the male population (i.e. around 66,000 people in Switzerland), with “considerable stigma and taboo” surrounding it, says Hakim Gonthier, the organisation’s director. “We work with people feeling immense distress, who don’t know where else to turn. How should they talk to their loved ones? We are often the only people who know what’s going on in their heads.”

The organisation offers them and their loved ones an attentive ear and supports them through a process of change that can take time. “We frequently observe that they tend to minimise the facts, through denial and cognitive distortions, i.e. they interpret children’s actions as an invitation. We help them to become aware of these fantasies, redefine them and explain what the laws are,” Hakim Gonthier says. However, the director offers some hope. “Taking the step of contacting us can protect them from acting on their impulses.” Dis No does not provide any sort of therapy but can refer people to experts if they are willing to go. However, therapists can be hard to find. They are often untrained or reluctant to work with these patients.

Between

of children know their abuser

As with perpetrators of sexual abuse, the majority of people who come to the organisation are men. Women who seek help from Dis No more typically suffer from paedophilia OCD – the “fear of being a paedophile” – as opposed to actually being attracted to children. The organisation is determined in its fight against the myths surrounding this disorder and reminds us that paedophilia is not the same as sexual assault. “Only 30% to 40% of people who have sexually assaulted children are estimated to have a primary or exclusive sexual attraction to children, which would classify them as paedophiles,” Hakim Gonthier says. “The remaining 60% do not fit with a paedophilia diagnosis but are opportunistic aggressors with a psychopath or antisocial profile.” He also recommends not stigmatising this attraction, as long as it is delimited within clear-cut boundaries and non-acting strategies and remains restricted to thoughts. “Contact someone before the situation gets out of hand. The shockwave is too intense for the victim, the person and their loved ones. Once the line has been crossed, there’s no turning back,” he says.

Marco Tuberoso from Espas works with perpetrators under age 18 referred by the juvenile court. The majority are boys, most of whom have also suffered abuse, and a third are victims of sexual violence. “However, this does not mean that all abuse victims become abusers,” Marco Tuberoso says. “For teenage perpetrators, sexuality is often a way of turning to a pattern of delinquency, showing just how bad they are doing.” In a gendered society where emotional expression is still excluded from the construct of masculinity (girls, on the other hand, are more likely to have self-destructive tendencies), the psychologist focuses on getting these young men to talk about what they are going through, while reminding them that having been abused does not entitle them to go out and attack someone else.

Re-educating society

Sexual violence is rooted in every stratum of a patriarchal society. No one, victim or loved one, is spared. It even impacts subsequent generations and must be understood as a matter of public health. Turning a blind eye or remaining silent to keep up good appearances of family and social relationships is punishable by law. This is also true for healthcare professionals. Those we interviewed feel that they still receive far too little training on these problems but nevertheless end up having to deal with the resulting tragedies. “We must dare to ask the question, open the door and let them in,” insists Francesca Hoegger. And Alessandra Duc Marwood concludes, “We need to re-educate society. We have a duty to listen to and protect the most vulnerable.”

“I didn’t want to be the one who destroyed the family”

Interview conducted by ÉMILIE MATHYS

“I was a victim of incest by my stepfather. It started around my sixth birthday – it’s a bit blurry – with touching. Over the years, it turned into rape. The abuse continued until I was 15, when my mother divorced him. As a child, I didn’t understand what was going on. My stepfather was the authority figure of the household and was very close to me. I was always the one with the most presents, the biggest room, allowed to sit in the front in the car. He was also very touchy-feely, even in public. But he could also be very manipulative and would cry and threaten to kill himself if I told on him. I was under a lot of pressure. Especially because I didn’t want to be the one who destroyed the family.

The first time I told anyone that I’d been the victim of incest was on my 16th birthday. I told two friends. They were shocked and didn’t know what to say. I don’t resent them for it, but I felt stupid and ashamed. So I remained silent. For a long time, I was in dissociation¹, but as the years went by, the weight of what happened to me felt increasingly heavy. Then the Covid-19 pandemic broke out and broke me too. It was too much. I had a ball of hatred inside me. I felt bitter towards everyone. My boyfriend at the time was the first person to listen to me. He urged me to talk to my brother, who I was very close to. He believed me. It was a huge relief.

With his help, I told some people in my family. Everyone was in shock. I felt relieved, but at the same time very alone. A lot of adults suspected something but didn’t do anything about it. And now everyone blames themselves. I reported him three days after I told everyone, in May 2020, following my father’s advice. As a former spouse, my mother was a suspect and found out from the police that my stepfather had abused me. I’m still waiting for the trial, which keeps being postponed². In the meantime, even though he’s no longer allowed to see my half-brother, my abuser is walking free. The justice system doesn’t do enough for victims. We should have more support.

I agreed to testify because I wanted to show that anybody can be a victim. No one is totally protected. Everyone knows someone close to them who has suffered abuse. And it’s important to feel that you’re not alone. Last year I founded the organisation Amor Fati, a support group in Fribourg for victims of sexual abuse. I’m also a psychology student. I hope that I’ll be able to help other people in the future.

¹ Episodes resulting from trauma during which the person is disconnected from one or more aspects of reality: their body, thoughts, environment and/or actions become foreign to them.

² Since then, the first part of the trial has taken place, and the prosecutor requested a 12-year prison sentence against the defendant. He has appealed.

About

of abused children never tell anyone

“You can transform your trauma into something positive”

Interview conducted by ÉMILIE MATHYS

“Yes, incest also happens to men. And talking about it doesn’t make you less ‘manly’. It’s important for us to be heard on this issue.

I was abused by two different people, which also means two different experiences. I was very young the first time, about 3 years old. We used to play mums and dads with my friends. An older girl, my cousin’s cousin, always wanted me to be the dad and her the mum. Once she took me to an isolated building and started touching me. It happened several times. I felt that it was unusual, weird, but I don’t remember anything violent.

Unlike the second person, who assaulted me. Back then, I was living with my aunt, in a very violent, very stressful environment. My cousin, who was 16 at the time, took advantage of me. Since I wasn’t part of the immediate family, she knew they would never take my side. She did everything to me, from touching to penetration. Threats and blackmail. I was so afraid of being kicked out of my aunt’s house that I did everything I could to make sure we wouldn’t get caught. The situation lasted a year. Then I moved out and in 2014 came to live with my uncle in Switzerland.

Due to my survival instinct, I never said anything. I put the whole thing in a box, and I sort of cut myself off from my emotions. But maybe they’ve expressed themselves in different ways. For example, I have at times felt disgust for women. I didn’t believe in love. However, I was constantly trying to get their attention. I’ve always been sensitive to violence, especially sexual violence against women. When they would confide in me, I’d want to say, ‘I know what you’re going through’. I felt powerless for a long time. I had this urge to show that I was the biggest, the strongest, and was totally into sports. I felt as though I was that little Prosper who had to keep quiet, as if my cousin still had a hold on me. I managed to transform that desire for ‘masculinity’ into something positive. I was even an amateur boxing champion in Switzerland. If I were to come across that woman today, I’d want to show her that, despite everything she put me through, I’m doing fine. I’m my own person.”

Maltraitance

![[Translate to Anglais:] ILLUSTRATION: ANA YAEL](https://www.invivomagazine.ch/fileadmin/_processed_/4/9/csm_psy_main_6167d7d863.jpg)